What stayed with me was the ship.

There were plenty of other memories too: Dennis Hopper’s Deacon losing an eye and then utilizing broken goggles as an eyepatch; the atoll and its tragically quick collapse under artillery fire; Jeanne Triplehorn’s Helen subjected to Swept Away (1974) levels of implicit and explicit violence (sexual, emotional, or otherwise).

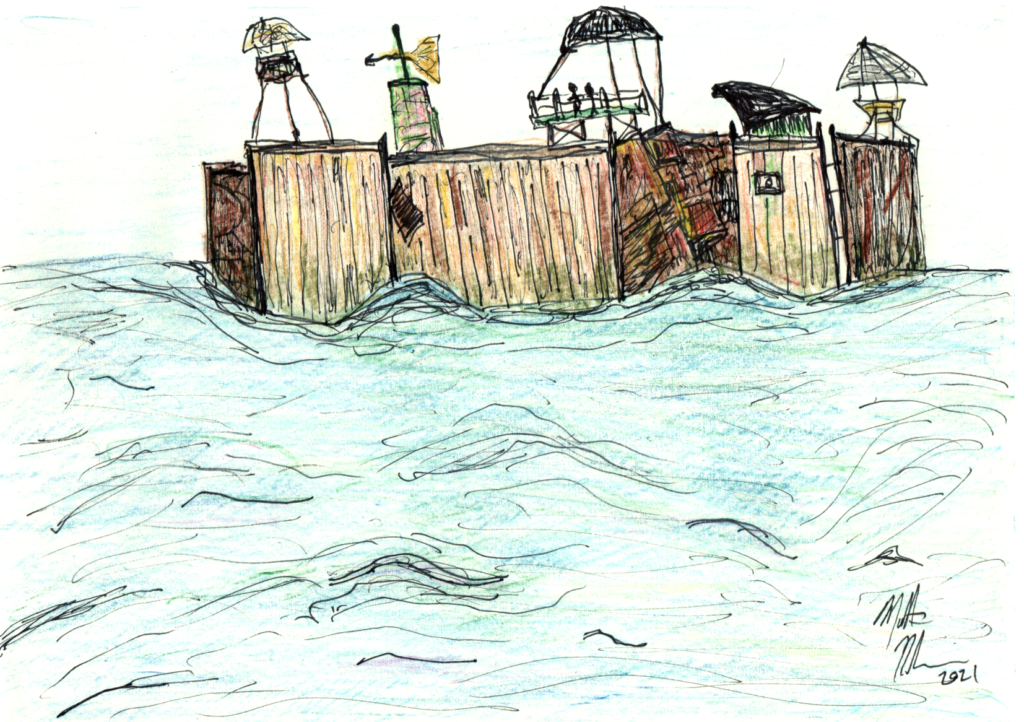

But those are all tied up in the contrivances of a crummy narrative and (according to trivia and gossip) countless rewrites near-disasters. The trimaran was what I latched on to in 1995 and what stayed with me through over two decades of Waterworld being a punchline. Like the unjustly maligned Ishtar (1987) and Blackhat (2015), I wonder how many people actually took the time to watch the movie before they piled on. Movie fans like to shorthand a movie’s success as box office or awards success, and like to use aggregate ratings as shorthand for experiential data. This has only gotten worse over time while also being subsumed in the streaming wars’ tendency to remove all context from films. But I’m off-topic. I’m talking about the ship, and how unbelievably fun it looks to be on that ship, on that ocean. The legacy of Waterworld should be its stunning panoramas and its movie stars.

I’ve always loved the sea, but I’m a native of West Virginia/Western Maryland who lives in Pittsburgh. So the sea has been attainable about once a year while traveling, but nothing more. A life goal is to live proximal to the sea. I have to assume that Waterworld, premiering when I was 13 years old, had a large influence on that goal.

Before I get back to being wistful about the sea, I do want to acknowledge the tonal inconsistencies and odd plot choices. The script is patchwork and the central narrative is undermined by the ending. My rewatch this week—the first time that I’ve seen the movie in 20 years—was the Ulysses Cut, which includes about 45 minutes of additional (and, in my opinion, highly necessary) scenes. The added footage provides motivation and shading for Helen. She benefits the most from this added footage, as we see why Helen is willing to put up with the godawful behavior of The Mariner. She and Enola were already on the verge of being expelled from the atoll before the attack by the Smokers, and she isn’t just a surrogate mother for Enola, she also is a disciple of a sort, placing all of her hope and faith in the idea that Enola’s mysterious tattoo really leads to Dryland.

The additional footage also benefits the Mariner’s story, as it allows for more time on the ship with Enola and Helen, and shows him bonding with Enola and learning to trust Helen. Unfortunately, this doesn’t change the ending and only makes that feel even more out of left field. What we see in the Ulysses Cut (and in the theatrical, based on my hazy memory and online synopses) is the Mariner growing as a person: he begins the film by breaking the mainmast of a fellow traveler, dooming the man to death by Smoker pirates. He follows this up with selling Helen’s body in exchange for some pieces of paper (to my adult eyes, I think that this scene had more nuance that was lost in bad writing, as I got the impression that the Mariner never planned to let the drifter rape Helen, but he wanted to distract him while he read the papers, as he immediately rescinds the offer after we see him read. HOWEVER, the behavior is still unconscionable and irredeemable.). But then the Mariner ends the main narrative by sacrificing his boat to save Helen and he attacks the Exxon Valdez to rescue Enola. He has grown to care about these people.

… Until the movie ends on Dryland, wherein all of his growth and trust and Helen forgiving his shitty behavior is undermined when he leaves and heads back out to sea. There’s a toss-off line at this point about him “trying to find more people like me,” but the entire story up to that point is about him becoming part of a social group with Helen and Enola. Leaving doesn’t line up with where the story developed, nor does it make sense on a practical level. All I can think is that they wanted to have him be like Mad Max, and leave society at the end, but Mad Max was always a drifter and he only helped others because of his principles. Mad Max drifted on afterward because that was who he was, and that was unchanged by the end of the adventure. The Mariner has an arc in which he changes as a person, so him leaving makes no sense.

These are the flaws with Waterworld. They are probably sufficient to keep it as an historical punchline, Kevin’s Gate as it was known, combining the crummy failure Heaven’s Gate with the fact that Costner spent almost $200 mil on this movie in 1995. But I think that we should take a cue from how people view another cinematic aesthete, Terence Malick. I’m not much of a Malick fan, but I think looking at Waterworld’s vistas, its costumes, its sound design, and its visceral thrills reveals a much better movie than if we were expecting something lean and internally consistent like Fury Road. Watching our protagonists cruise across the wide Pacific, and watching them haggle over drinks of water and a few lime leaves… the movie is dripping with the sublime in ways not dissimilar to Malick’s beloved The Thin Red Line, just adorned in the trappings of a George Miller film.

I’m not saying that 13-year old me got it right and everyone else got it wrong. But I challenge anyone to fire up that blu ray on a big tv, with the speaker bar nice and loud, and not get swept up in the dazzling blues and salt-crusted browns of this movie. There are countless moments where Costner swings on a rope from one side of the trimaran to the other and then turns the wheel or unfurls a sail, and there’s just no way it was a stuntman. There’s a lot of joy in the busywork in the movie, and I found myself charmed repeatedly by it. I’d like for Waterworld to be remembered for these pastoral (pelagic?) moments. That’s what stuck with me, and what will stick with me until 25 years from now when I watch it again.

(This time hopefully from an ocean-adjacent locale.)